- Home

- Mary Williams

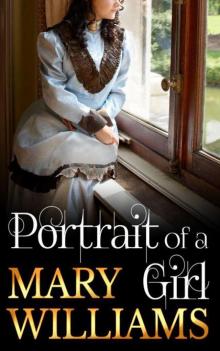

Portrait of a Girl Page 3

Portrait of a Girl Read online

Page 3

Having expected to find someone more of Mrs Treen’s type, I was bewildered by this first glimpse of the quaint creature who appeared more suited to be a character in a play than in real life. Her voice, too, was light and high, but I guessed could be sharp if she felt like it.

Conversation between the three of us was short. Indeed after the first introduction and intimating of my expected behaviour and duties, Rupert Verne appeared anxious to leave.

‘The horses will be getting restless,’ he said. ‘The light’s bad, and my wife likes dinner to be punctual. First, though, I would like to show you my — collection. Dame Jenny has been its previous guardian for many years. In future you will share the duty. Dame Trenoweth—’ he indicated the parlour door with a wave of his hand, ‘you first please, and we’ll follow.’

The red slippers made a tapping noise, the necklaces and silk dress tinkled and rustled as the tiny figure led us through the hall to a door on the right, further down. The surround was arched, and the wood, of light oak, was panelled and carved in a symbolic and intricate design. From a pochette hanging at her wrist Dame Jenny took a bunch of keys, she inserted one in the lock, and we went into the room. It was larger than I’d expected, and at some time in the past, obviously, had been converted from perhaps two smaller ones of plain architecture into an interior of intriguing nooks and alcoves.

Candles had already been lighted, throwing fantastic shadows about the treasures stored there — French figurines, music boxes, ivory miniatures in velvet frames, and paintings of exquisite beauty; the walls were silver grey, the ceiling blue and one wall comprised entirely of a large white marble fireplace with settles round it for seating.

It was not possible at first glance to absorb details. The rosy glow of burning logs and candles emphasised the air of mystery and days long ago — countless years in which the treasures must have been collected. There were paintings — mostly water-colours of landscapes that seemed to quiver with life as transient shadows crossed their surface. The delicate poised figure of a glass dancing piper flashed with rainbow movement when I took a step forward, disturbing the quiet air. Then it was stilled again into shadow. I stared round wonderingly, then glanced back again to the fireplace because above it was the focal point of the whole room.

A portrait.

The painting of a girl with upswept silver-pale gold hair tied high with a green ribbon. Her face was heart-shaped from which hazel eyes stared with the translucent quality of moorland pools lit briefly by sunlight. The mouth appeared on the verge of laughter but the whole effect was of longing — the longing and sadness of beauty unfulfilled. I was fascinated, briefly magnetised, sensing that the surroundings were merely a background, perhaps a dedication, to her personality. Above a froth of lace her slim neck held an opalescent glow, ivory pale, yet changeful in the flickering candlelight with all the glowing radiance of waves breaking gently on a cool shore.

Who was she, I wondered? Envy stirred me for a moment, because I felt instinctively she must somehow, in some secret way, hold a place in Rupert Verne’s life.

‘What a lovely portrait,’ I heard myself saying ineffectually.

‘Yes.’ The one word fell short and curtly from his lips. I glanced at him expectantly. ‘Is it anyone —?’

‘You’ll never meet her,’ he interrupted. ‘It’s just a good painting, and the setting is right. That’s why it’s there.’

‘I see.’ But I was disappointed; I felt he could have told me so much more. His expression, I noticed, had tightened. There was a bleak guarded look in his eyes and in the set of his mouth that told me I trod dangerous ground and should stop questioning.

So I said no more on the subject. More practical matters were discussed in which I learned I would not be seeing Signor Luigi until the end of the following week, when the chaise would arrive to take me to Truro.

‘Dame Jenny will have time to see that your clothes are in order and suitable for your introduction,’ he added before leaving. ‘She’s an excellent needlewoman, and if anything is required word can be sent to Kerrysmoor. Jan Carne will bring a message.’ I wondered who Jan was, but didn’t ask.

‘That’s right,’ the old lady said, nodding her head briskly several times. ‘These old fingers of mine mayn’t be as nimble as they once were, but I can still sew a seam or tuck, and put in a daisy or two when needed.’

Her cheeks had turned very pink; she reminded me of a bedecked robin inquisitively inspecting its domain. I noticed also that her thin ringed hands had a tremor. No wonder Mr Verne no longer considered her quite capable of safely dusting and moving the treasured figurines and curios in the room we’d just left. I had misgivings myself when I considered the responsibilities were in future to be partly mine.

Minutes later Rupert was at the door saying farewell. He held the tall beaver hat in his hand a second before replacing it on his head, turning, and walking briskly away down the path to the waiting chaise. During that brief second his eyes held mine again while excitement churned in me — an electrical awareness of communion binding all the nerves of my body into a hungry fire of desire.

Against my will I made a slight instinctive movement towards him. Did his left hand make a faint gesture of acknowledgement beneath the lace cuff? Just for that fleeting instant did the lines of his stern mouth soften? — the lids quiver over the long golden eyes? I shall never know. My head and senses were whirling so that imagination became confused out of focus with reality.

When my heart had steadied he was already at the gate. A minute afterwards he was ensconced in the chaise, and the vehicle, following a flick of the coachman’s whip, was moving down the shadowed lane, throwing a zig-zag of fading light before it, from the swaying lamps.

Evening had faded into deep dusk. When we moved into the hall again Dame Jenny took me up a narrow staircase to my bedroom. The walls were all of white, the furnishings of light oak in an old world style. There was one window overlooking the garden at the back of the cottage. After the old lady had gone I pulled the curtains and looked out. The deep velvet blue sky was already pin-pointed by starlight, but the night was not yet dark enough to obscure the looming shape of the hill rising formidably against it. There was something else too — which I thought at first was probably my imagination. But in the morning I knew my conjecture to be true. Three gaunt shapes stood at a different angle from my first glimpse of them — silhouetted in the morning light.

The Three Maidens.

There was no practical reason why I should have sensed an omen in their presence. But I was filled with momentary, irrational depression. Why? A second later I’d dispelled it. I was, after all, half Welsh, half Breton, which could be the reason for my Celtic mood.

It was the only sensible answer and one I made myself accept.

Chapter Two

During those first few days at Tregonnis, Dame Jenny was completely non-communicative about matters concerning Kerrysmoor or the Verne family, and when I questioned her about the history of the cottage and priceless valuables of the ‘treasure room’, she became stubbornly silent — almost hostile.

‘None of your business, miss,’ she said in her thin piping tones. ‘All you have to do is help me, as the master said — take down anything that needs dusting so there’s no danger of it falling, and polishing — those fancy chairs’ legs need attention. ‘Tisn’t so easy any more for me to bend or get down on my old knees. I keep the key of the room myself. Every morning I take a look round, so see you’re about between ten and eleven, an’ I’ll be able to let thee in.’

‘Yes, Dame Jenny,’ I agreed meekly.

She nodded, adding, ‘You can help me with the baking too. There’s an apron in the kitchen to cover all those fancy things you do wear. Then soon as possible we’ll get to thinking ‘bout what stitching’s to be done to make thee presentable for meeting the music man.’

I smiled to myself at her reference to Signor Luigi as ‘the music man’.

‘Hope you know how

to use the needle properly,’ she added. ‘I was always one with a liking for dainty flowers and tucks. But, of course, your cape must be quiet and moderate, I’ve a piece of brown velvet upstairs might do. No use worrying the master for gold to waste on material when it’s there safely folded in my chest upstairs. Still, we’ll see ‘bout those things a bit later; maybe tomorrow. You take things easily today, girl, get used to the cottage an’ garden. Done any prunin’ or weedin’, have thee?’

I shook my head. ‘No. In Falmouth we didn’t have a garden.’

‘Hm. Well, there’ll be bits to do here. But never touch my roses, mind. Roses is delicate things that need dainty handling. With care I have them bloomin’ most all the year round. Even at Christmas I’ve known red buds openin’ to cheer the winter.’

When I went out to the back later I discovered that she had in no way exaggerated. On one side of a path comprised of pebbles and small rocks of granite quartz reflecting different shades, in the early morning sunlight crimson roses blossomed, mingling colourfully with bronze and gold chrysanthemums.

On the other side, half shadowed by drooping willow, water-lily leaves dappled the surface of a motionless pool. It appeared deep, reflecting the shape of a poised white marble statue at the far end — that of a woman emerging from reeds and ferns, staring into the water. She had one arm over a breast, a bowl or kind of urn held in the other, from which delicate plants trailed. Much of the figure was lost in the verdant undergrowth, but the evasive light gave an uncanny impression of life and momentary movement. The whole effect emanated an emotional quality that affected me oddly.

I tore my eyes from the pool and glared up at the great hill behind. The morning light emphasised the rugged character of the rising moor — great boulders and clumps of heather and gorse, interspersed with the inky grassy darkness of bog and gaping shafts. A derelict mine stack stood halfway down below the Three Maidens. Not a pleasant vista exactly — primitive, intimidating almost, in its wild aloofness, yet challenging, and I knew, despite Rupert Verne’s warning, a day would come when I would set out in exploration.

Meanwhile I determined to make every effort at pleasing the quaint keeper of Tregonnis, and managed to acquire a certain amount of trust from her, though her old eyes had a watchful look whenever I strayed beyond the garden gate.

‘Ye recall what the master told thee—’ she said one day. ‘Keep away from the hill. There’s plenty of interest in the garden since you like fresh air, and I can teach thee a deal ‘bout herbs from my own small patch — it’s at the side beyond the roses. There’s some bunchings to do before drying — your hands look nimble enough. And what about your voice? I haven’t heard any singing yet to speak of — just that humming when you’re in the treasure room. There’s my fiddle to accompany you when you feel like practising. I was good on the strings in my day.’

I didn’t attempt to explain to her that all her fussy restrictions quelled any natural impulse to burst into song, or that her country style of fiddling would only put me off. However, she didn’t press the point, but insisted on me putting certain hours of every day into stitching at my ‘wardrobe’. The velvet material was used for a cloak-coat with velvet band trimmings. The material was sent to Truro to be cut by a costumier patronised by Lady Verne and sent back to Dame Jenny for making up. This was a tiring business for me, and my day-dress of green silk to be fixed over a moderate bustle, was more so. It had an apron front and white lace collar. There was a good deal of piping to do, and numerous tiny buttons to sew on. Dame Jenny was certainly nimble with her fingers. If she hadn’t been I should have been working day and night, because in the past I’d worn mostly colourful shawls to cover hastily converted gowns. Inwardly I fumed and fretted; how much easier and more relaxing it would have been to have taken Rupert Verne’s offer of buying clothes from a professional establishment.

I liked the headgear. It was re-styled, hardly a bonnet, hardly a hat — with small flowers and bows on it, and was a relic from the old lady’s chest where she kept precious nick-nacks of her own stowed away. A single white plume curved neatly round the back of the crown, with a shred of veiling floating behind. Tilted precociously forward on my coiled upswept hair it looked quite intriguing. Dame Jenny nodded cautiously when I turned from the mirror to face her.

‘It will do, I suppose,’ she said one afternoon with a hint of criticism in her voice. ‘A little saucy, but then you’ve that air about you. So long as you do keep your eyes fixed down modest-like we must hope it won’t offend. I’ve heard tell those Italians, singers and such-like, go in for a bit of show. A little rice powder on your cheeks will help make you less — colourful.’ Her lips closed primly on the last word.

I laughed; I couldn’t help it. Everything — the whole situation, the future, the old lady’s grudging admiration and the thought of extending a gloved hand to Signor Luigi like any duchess stirred pleasurable excitement in me. I felt my throat trembling, and without warning joyous notes of solfa rose from my lips, turning involuntarily into a song — a song of mountains and rivers, of far off places and unknown passion luring me to the sweet rich fulfilment of love. I was trilling in the only way I knew — naturally, with abandon. My voice was firm, and full and sweet, realising all the longing I’d felt during the last few weeks for Rupert Verne.

When the sound died and I waited hesitantly with my bosom rising and falling breathlessly under my bodice, there was a prolonged pause from the old lady. She stood simply staring before remarking: ‘You certainly have a pair of good lungs, girl. But if you take my advice you’ll remember to control them in a ladylike fashion when the time comes to meet the great man. No doubt in low class hostelries, sailors and drinking folk ‘ppreciate a deal of show and noise — but any famous acquaintance of the master will expect a taste of refinement.’

‘Oh, but I have to sing as I feel,’ I told her bluntly. ‘Refinement or — or coarseness doesn’t come into it. If I had to be controlled and careful there’d be no song—’ I broke off with a tinge of doubt rising in me, and it was at that moment the door creaked, sending a wave of cooler air into the parlour.

Startled, I looked round. Mr Verne stood there, top hat in one hand, wearing a black broadcloth cut-away coat with a cape slung over the other arm. His watchful eyes had a concentrated enigmatic look in them, but I fancied there was a tilt of approval round his mouth, and I was once more conscious of his strange sense of power, of an awareness between us that set my pulses leaping with wild restrained joy.

‘Practising already?’ he said in level tones. ‘Good. In two days’ time we go to meet Signor Luigi.’

‘Two days?’ I echoed. ‘I thought—’

‘If you’re ready, that is,’ he added and turning to Dame Jenny remarked, ‘providing the dress-making session permits. At the moment I must say you look — quite charming.’

Dame Jenny appeared slightly flustered.

‘If I’d known you were calling today, master, I’d have had things more shipshape. This is only a try on. There be gloves and all manner of little things to ‘tend to, and a few alterations. And—’ with quite a stern glance at me, ‘no more interruptions of tra-la-ing.’

He allowed himself to smile then. ‘Oh, I’d call what I heard at the gate more than tra-la-la-ing. Surely you with your knowledge of good music must appreciate that, Mrs Trenoweth?’

Mollified, she replied, ‘Good music? I’m not all that well versed in such as opera, Master Verne. The fiddle’s more to my taste, as it was to my father and his before him. But if you ‘ppreciate my young lady’s voice then good it must be, I’m sure.’

Shortly after that brief interim of conversation between us, Mr Verne left. There was a further flurry of the dressmaking session, during which I was content to keep silent in case I betrayed my secret feelings to Mrs Trenoweth. Excitement gradually calmed to a deep glowing happiness that held no thought of the past or morrow, or the strange circumstances that had brought me into contact with Rupert. No impossible pl

ans for the future stirred me. He was married, and not the type of man to treat any woman lightly. If he had been I wouldn’t have admired — longed for him so passionately. To have visioned any outcome could have been ridiculous. As it was, a few precious moments in his presence were sufficent to make the day glow — the sun more bright, the skies over the wild autumn landscape a clearer more translucent blue.

When the prodding, pinching and pinning were over and the bustle adjusted perfectly into place Dame Jenny, at last tired herself, suggested I might like a breath of fresh air. ‘There’s not much to do in the kitchen,’ she said, ‘the baking’s over, and Jan comes tomorrow to clean the floors. Take a stroll if you want to, girl. Only don’t thee go wanderin’ ’bout that hill. Remember, or there’ll be trouble. Understand?’

I nodded, and promised I’d take the valley lane towards the village.

It was a dazzling day, speckled with frail misty air that dappled trees and undergrowth with shimmering light. The damp earth smells were redolent with the odour of fallen leaves and tumbled ripe blackberries; there was no wind, and the extreme silence — broken only by the flap of a solitary bird’s wings or scuttle of some small wild creature from the bushes, emphasised autumn’s magic. It had been the same when I was a child — only then the salty tang of sea mingled with all the other odours of dockland — of malt, fish, and crowds swarming round newly berthed ships had filled my young nostrils nostalgically reminding me my father Pierre would appear any day, bringing some exciting gift for his Princess.

Lost briefly in reminiscences of the past I came to the curve at the base of the hill which led in one direction towards Kerrysmoor along the route I’d driven with Rupert in the chaise. I had turned the corner when the rattle of horses’ hooves and wheels approached from the opposite direction. Quickly I stepped aside and stood motionless against a hedge of willow and thorn, waiting for it to pass.

The Lost Daughter: A Memoir

The Lost Daughter: A Memoir How to Be a Perfect Girl

How to Be a Perfect Girl The Velvet Glove

The Velvet Glove Portrait of a Girl

Portrait of a Girl